Teachers’ Untapped Potential: A Conceptual Synthesis of Teacher Leadership

Jetë Aliu

Faculty of Education, University of Prishtina

Abstract

Teacher leadership is a critical component of school change, yet it remains a concept with a lack of consistent definition. This ambiguity in the literature is compounded by a practical gap in teacher preparation. This paper constructs a holistic conceptual understanding by synthesizing the literature on teacher leadership. It argues that while the scholarly literature defines teacher leadership as a broad, multi-faceted process with significant outcomes at the school, teacher, and student levels, initial teacher education often cultivates a "narrow view" of leadership and teacher’s role in school development. This view is usually confined to formal, individual, and classroom-level roles, creating a gap between the concept of teacher leadership and the preparedness of future teachers to enact it. The paper concludes by discussing the implications of this gap and the critical role initial teacher education must play in shifting the conceptualisation to unlock the full potential of teachers as leaders.

- Introduction

The teaching profession has become increasingly complex in the last decades particularly during the times when schools are facing dynamic societal changes and demands for quality education. In these challenging contexts the traditional, top-down model of principal-centric leadership has proven inefficient as one person alone cannot handle everything within the school. This has led to the rise of distributed leadership models (Spillane, 2006), where effective leadership is seen as an emergent practice involving multiple actors. Within this paradigm, the "invisible power" of teachers as leaders is recognized as a significant component of school change (Wenner & Campbell, 2017). Teachers are uniquely positioned to influence their colleagues, shape school culture, and drive improvements in teaching and learning.

Despite this, teacher leadership as a field of study has been described as "largely atheoretical" (York-Barr & Duke, 2004, p. 291). Decades of scholarship have produced overlapping and competing definitions (Harris, 2003), and this challenge persists, with recent reviews of the literature demonstrating lack of a common and ubiquitous understanding of the concept (Aliu et al., 2024). This conceptual ambiguity creates a significant problem in preparing future teachers for the new paradigm of the teaching profession. Today’s teachers are expected to actively participate in overcoming the daunting challenges that schools face nowadays.

This conceptual challenge points to another, more practical problem related to teacher readiness for leadership during their pre-service preparation. In their empirical research, Aliu & Kaçaniku (2023) demonstrate a readiness gap in future teachers for leadership by concluding that pre-service teachers' understanding of teacher leadership is based on a contextually drawn vision of what it means to be a teacher, resulting in a narrow view of leadership regarding it more as an individual and classroom level role. This indicates that while the profession needs teachers to be leaders, the educational system may be falling behind to cultivate the necessary identity and skills from the start.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to build a conceptual framework that bridges the gap between the scholarly concept of teacher leadership and the practical preparation of teacher leaders. To do so, this paper will:

- Define and conceptualize teacher leadership based on extant literature.

- Summarize the known outcomes of teacher leadership at the school, teacher, and student levels.

- Analyze the readiness gap in pre-service teacher preparation.

- Discuss the implications of this gap and the role of initial teacher education in bridging it.

- What is Teacher Leadership?

The concept of teacher leadership remains a concept with a lack of consistent definition in the literature. Literature regards it in various forms ranging from a formal role in the school hierarchy to an informal role of influence towards colleagues, professional development, and school improvement. A myriad of definitions exist in the literature describing teacher leadership. Katzenmeyer and Moller (2009) state that teachers who assume leadership roles inside and outside of the classroom, persuade colleagues to enhance educational practice and support the community of teacher learners, are considered teacher leaders. York-Barr and Duke (2004) define teacher leadership as the process in which teachers individually or collectively influence their colleagues, principals, and other members of school communities to improve teaching and learning practices. Teacher leadership relates to teachers’ behaviors toward school advancement, professional development, collaboration with colleagues, and their knowledge, skills and behaviors for improving teaching and learning (Harris & Muijs, 2005). This suggests that teachers’ leadership readiness and attitudes are important in elevating the quality of instructions taking place in schools and as such the quality of education delivery to students.

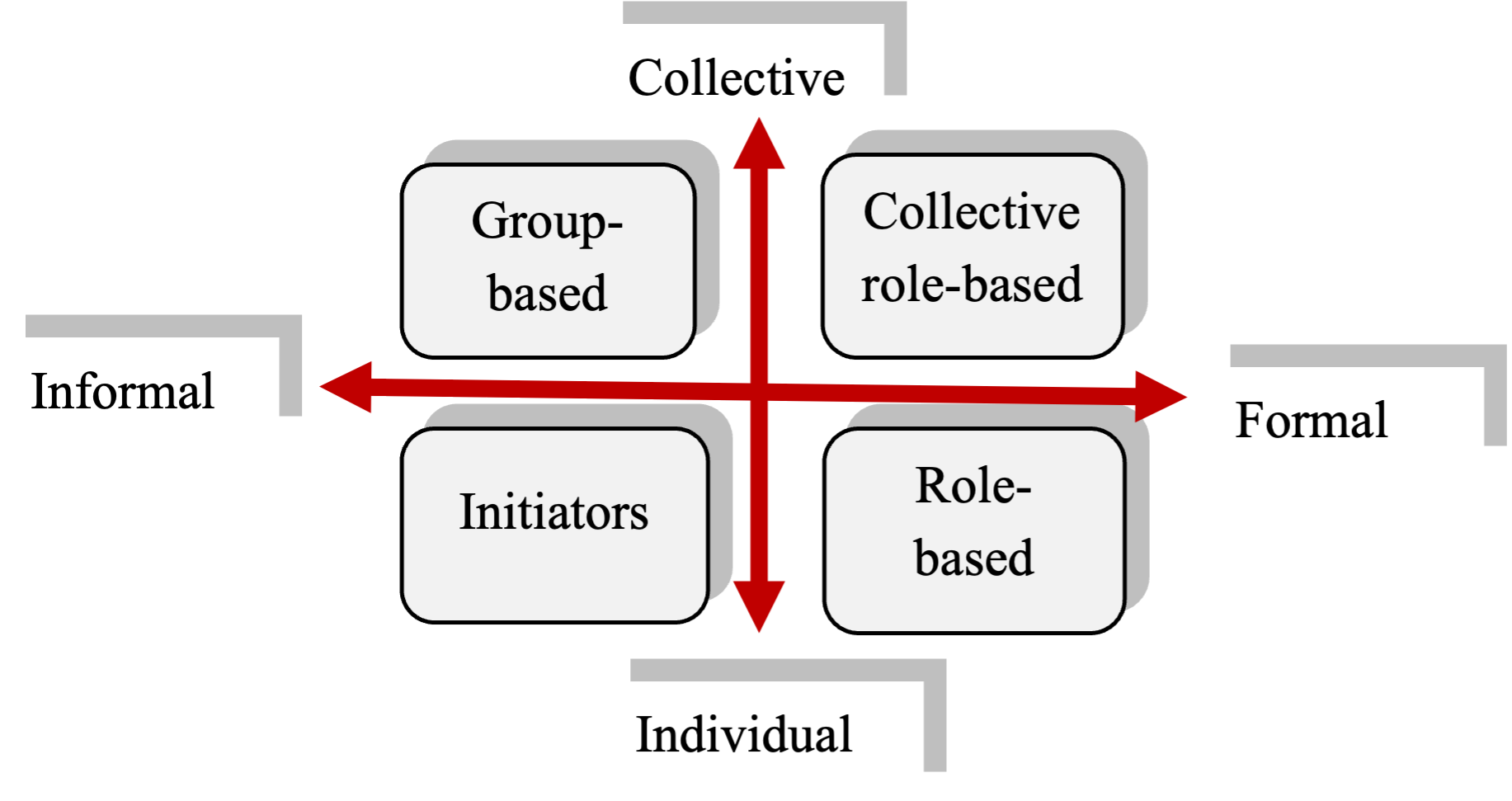

These existing definitions highlight that teacher leadership is not a singular hierarchical position, but rather a multifaceted process based on influence, behavior, capability, and responsibility (Wenner & Campbell, 2017). To better categorize these various conceptualizations, the framework developed by Snoek et al. (2019) is invaluable. As illustrated in Figure 1, it organizes teacher leadership along the aspects: Formal vs. Informal and Individual vs. Collective. This creates four distinct types of teacher leadership:

- Formal and Individual (Role-based): Teachers are given a specific position by school authorities (e.g., coordinator, team leader, department chair). Their authority is formal and recognized in the school hierarchical structure.

- Formal and Collective (Collective role-based): Teachers work together as part of a group with a formal, specific role or mandate (e.g., a curriculum development committee, a school improvement team). They work collectively to influence others outside of the group with a particular objective related to school improvement.

- Informal and Individual (Initiators): Leadership arises not from a formal position, but from a teacher's personal initiative, competence, or experience to contribute to school development (e.g., creating an informal study circle, mentoring a new colleague). They have an influence on others because of their personal characteristics and initiative.

- Informal and Collective (Group-based): Teachers work together collaboratively on initiatives that support the school. In this "community-based" approach, leadership is fluid and attributed to those with the most relevant expertise for a specific task. This type regards teacher leadership as fluid as leadership moves to individuals considered most appropriate for a particular occasion as circumstances evolve.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework of Teacher Leadership (Snoek et al., 2019).

Importantly, recent analyses of the field find that studies predominantly conceptualize teacher leadership as an informal and individual form of leadership (the "initiators" approach), highlighting a "shift from formal senior, administrative, and positional leaders to informal, regular teachers who do not have any official position" (Aliu et al., 2024, p. 399). This modern understanding emphasizes that influence is earned by the respect and trust other colleagues have, not simply granted by a title. Indeed, as Liang & Wang (2019) note, assigned functions can provide legitimacy but not necessarily influence. This distinction is vital, as it suggests that the most common and perhaps most authentic form of leadership is also the least formally recognized.

- What are the Outcomes of Teacher Leadership?

Understanding this multi-faceted conceptualization is critical because the practice of teacher leadership is directly linked to a wide range of positive outcomes. Efforts to stimulate teacher leadership are justified by its impact at various levels which ultimately support school development. The impact of teacher leadership be structured into three levels (Aliu et al., 2024):

- At the School Level: Teacher leadership is a key driver of school development and innovation and change. Teacher leaders allow for new practices to spread across the school (Akman, 2021) which then directly contributes to the creation of an effective school culture (Araşkal & Kılınç, 2019). They also foster healthier relationships developed based on trust and collaboration, which leads to an overall transformed school culture (Pineda-Báez et al., 2020).

- At the Teacher Level: Teacher leadership serves as a powerful feature for their own and colleagues’ professional development. Teacher leaders enhance collegial collaboration because when they engage in leadership, they share their ideas about instructional practices (Landa & Donaldson, 2020), mentor colleagues, and model reflective practice. This, in turn, leads to improved instructional practices across the school and this produces a higher sense of teacher self-efficacy (Kılınç et al., 2021) as well as motivation among staff.

- At the Student Level: Ultimately, the main purpose of teacher leadership is to improve students' achievement (Carpenter & Sherretz, 2012). This is the "main goal" of the teacher-leader. Teacher leaders contribute to enhancing instructional practices and developing a collaborative positive school culture. These elements have a clear, positive impact on student achievement and improved student motivation (Araşkal & Kılınç, 2019).

These outcomes demonstrate that teacher leadership is not merely an administrative function, but it is a mechanism that ignites professional growth and school improvement. The findings highlight the fact that teacher leadership is not a matter of preferred role, but rather an integral part of teachers reinvented professionalism.

- The Critical Gap: Pre-Service Teacher Readiness

The significant benefits of teacher leadership are contingent on having teachers who are willing and able to perform the multi-faceted leadership roles to contribute to school improvement. However, a significant gap often exists between the robust conceptualization of leadership in the literature and the practical preparation of teachers to enact it. This disconnect is particularly problematic because initial teacher education is the critical period where professional identity is formed (Sachs, 2005). The values and beliefs students develop become the foundation for their future professional decisions (Bullough, 1997). This formation period is precisely when initial teacher education should be nurturing the confidence and willingness (Muijs & Harris, 2006) to act as change agents and cultivating a clear personal philosophy to education (Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2009). Teacher education institutions have a particular responsibility (Forster, 1997) to design curricular experiences that build both the leadership identity and the specific competencies—such as collaboration, communication, and intrinsic motivation (Oppi et al., 2020)—required to effectively function in that capacity (Forster, 1997).

Empirical research highlights this gap between the concept and the preparation in the context of Kosovo. For example, a study conducted by Aliu & Kaçaniku (2023) with pre-service teachers aiming to explore their conceptualization of and readiness for teacher leadership revealed the following findings:

- A Narrow, Formal View: The predominant understanding among the interviewees situates the teacher leader in a formal and individual leadership stance. This positions their understanding squarely in the "role-based approach." Leadership was associated primarily with the "top-down outlook" of the school principal, who was seen as the key person responsible for school leadership. This indicates a hierarchical view of leadership that runs counter to the collaborative, informal models identified in the literature.

- Confined to the Classroom Borders: When asked about their own leadership, pre-service teachers confined it to being a ‘successful classroom leader' capable of effectively fulfilling the curriculum requirements. Their focus was on "effective classroom management," "contemporary teaching methodologies”. While being able to effectively identify essential skills for students’ academic achievement, leadership role was rarely connected to a broader collegial or school-level influence.

- A Missing Link between Teachers and School Leadership: This demonstrates a "missing link between teachers as individuals and the school leadership structure. The informal, collective, and initiator-based roles were marginally represented or missing from their understanding. Even concepts like collegiality were primarily understood as sharing practices for individual classroom use, not as a collective effort for school-wide change.

These findings point to a major disconnect between the theoretical understanding of the role and benefits of teacher leadership and the reality of teacher preparations for such roles. Literature demonstrates the importance of teachers acting as leaders for the school development, yet the next generation of teachers is being prepared with a narrow view of their role and contribution confined within classroom borders.

V. Discussion and Conclusion: Bridging the Gap

This synthesis reveals a critical gap between the concept of teacher leadership and its cultivation. This is not merely an academic discrepancy, but it has profound practical consequences. If future teachers are not prepared to see leadership as a core part of their professional identity, they are unlikely to take on the leadership roles that literature shows are essential for school improvement (e.g., Harris & Muijs, 2005; Leithwood et al., 2008; York-Barr & Duke, 2004). As a result, the significant outcomes at the school, teacher, and student levels, ranging from improved culture to higher student achievement (Aliu et al., 2024; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2019), will not be fully realized. The "invisible power" of teacher leaders will remain invisible and untapped.

The empirical findings suggest that this gap is often a product of teacher preparation (Aliu & Kaçaniku, 2023; Antony-Newman, 2023). Pre-service teachers' contextually drawn vision of the teaching profession is shaped by their education. When future teachers develop a limited understanding of the roles and responsibilities of school leadership, their future engagement as leaders might be hampered because their identity is being formed around the isolated views of individual and formal leadership, often in isolation from the collaborative realities of the profession (Aliu & Kaçaniku, 2023).

This paper concludes that initial teacher education has a critical role in contributing to shifting the conceptualisation of teacher leadership beyond the narrow sense of individual and formal leadership. Teacher leadership cannot be an optional add-on as this feature of school culture and education functioning is imperative for school development. Therefore, teacher leadership must be placed within a wider context of teacher professionalism (Wenner & Campbell, 2017) from the very beginning of a teacher's journey.

To bridge this gap, initial teacher education programs should incorporate a more explicit and multifaceted approach to leadership and the role of teachers as leaders (Lieberman & Friedrich, 2010). This requires moving beyond theoretical discussions of classroom management and practically exposing pre-service teachers to leadership situations, such as collaborative projects, mentorship roles, and action research, in order to develop a broader understanding of the scope of teacher leadership, develop teacher leadership competencies and enhance their readiness to enact leadership roles (Aliu & Kaçaniku, 2023; Oppi et al., 2022). Furthermore, teacher preparation programs should focus on developing the generic skills and well-rounded personal philosophy to education (Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2009) that underpin leadership qualities, such as communication and research skills and a willingness to take risks. By situating teacher leadership within the broader frame of teacher professionalism and embedding it purposefully into pre-service curricula, teacher education can move from preparing effective instructors to cultivating proactive, collaborative leaders of learning. Only then can schools truly realize the collective potential of their teaching force.

References:

Akman, Y. (2021). The relationships among teacher leadership, teacher self-efficacy and teacher performance. Journal of Theoretical Educational Science, 14(4), 720–744. https://doi.org/10.30831/akukeg.930802

Aliu, J., & Kaçaniku, F. (2023). An Exploration of Teacher Leadership: Are Future Teachers Ready to Lead? CEPS Journal, 13(4), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.1634

Aliu, J., Kaçaniku, F., & Saqipi, B. (2024). Teacher Leadership: A Review of Literature on the Conceptualization and Outcomes of Teacher Leadership. International Journal of Educational Reform, 33(4), 388-408. https://doi-org.tc.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/10567879241268114

Antony-Newman, M. (2023). Teachers and School Leaders’ Readiness for Parental Engagement: Critical Policy Analysis of Canadian Standards. Journal of Teacher Education, 75(3), 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871231199365

Araşkal, S., & Kılınç, A. Ç. (2019). Investigating the factors affecting teacher leadership: A qualitative study. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 25(3), 419–468.10.14527/kuey.2019.011 (ERIC).

Bullough, R. V. (1997). Becoming a teacher: Self and the social location of teacher education. In: B. J. Biddle, T. L. Good, & I. F. Goodson (Eds.), International handbook of teachers and teaching (pp. 79–134). Springer.

Carpenter, B. D., & Sherretz, C. E. (2012). Professional development school partnerships: An instrument for teacher leadership. School-University Partnerships, 5, 89–101.

Forster, E. M. (1997). Teacher leadership: Professional right and responsibility. Action in Teacher Education, 19(3), 82–94.

Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: Heresy, fantasy or possibility? School Leadership & Management, 23(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000112801

Harris, A., & Muijs, D. (2005). Improving schools through teacher leadership. Open University Press.

Katzenmeyer M., Moller G. (2009). Awakening the sleeping giant: Helping teachers develop as leaders (3rd ed.). Corwin Press.

Kılınç, A. Ç., Bellibas, M. S., & Bektas, F. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of teacher leadership: The role of teacher trust, teacher self-efficacy and instructional practice. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(7), 1556–1571. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2021-0148

Landa, J. B., & Donaldson, M. L. (2020). Teacher Leadership Roles and Teacher Collaboration: Evidence From Green Hills Public Schools Pay-for-Performance System. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 21(2), 303–328.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060

Liang, J.,&Wang, F. (2019). Teacher leadership? Voices of backbone teachers in China. Journal of School Leadership, 29(3), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684619836826

Lieberman A., & Friedrich, L. D., (2010). How teachers become leaders: Learning from practice and research.Teachers College Press

Muijs, D., & Harris, A. (2006). Teacher led school improvement: Teacher leadership in the UK. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 961–972.

Nguyen, D. , Harris, A. and Ng, D. (2019). A review of the empirical research on teacher leadership (2003 - 2017): evidence, patterns and implications. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(1), pp. 60-80.https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-02-2018-0023

Oppi, P., Eisenschmidt, E., & Stingu, M. (2020). Seeking sustainable ways for school development: Teachers’ and principals’ views regarding teacher leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 26(4), 581–603.

Pineda-Báez, C., Bauman, C., & Andrews, D. (2020). Empowering teacher leadership: A crosscountry study international. Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(4), 388–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1543804

Sachs, J. (2005). Teacher education and the development of professional identity: Learning to be a teacher. In P. M. Denicolo, & M. Kompf (Eds.), Connecting policy and practice: Challenges for teaching and learning in schools and universities (pp. 5–21). Routledge.

Snoek, M., Hulsbos, F., & Andersen, I. (2019). Teacher leadership: Hoe kan het leiderschap van leraren in scholen versterkt worden? [Teacher leadership: How can the leadership of teachers in schools be strengthened?]. Hogeschool van Amsterdam.

Spillane, J. P. (2006). Distributed Leadership. Jossey-Bass

Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316653478

York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255–316. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074003255